A challenge for airplane people that write and fly for a living is that we never know when inspiration will come. You hope it comes when you aren’t too busy. This piece started while I was facing backwards (in the backward facing seat) of an air ambulance on a steep climb.

Safe? Statistically no. Not compared to the airlines. Am I typing, thinking and breathing comfortably? You bet. Aside from the turbulence from the wind rushing over the Sierras to our West and the sliding out of my seat from the rather steep deck angle, I’m fine.

The plane climbs with enthusiasm when nurse, patient and EMT have been dropped off and we’re returning the airplane mostly empty to its home in Nevada.The reality of turboprop and propeller driven aircraft is that they are statistically plagued with more accidents, but not for any reason I have to worry about tonight. Everyone that works here is a misfit for the airlines, will never wear bars on their shoulders or that crisp hat in an airline terminal with a roller bag festooned with stickers.

The guy flying? An air force veteran that flew the F-117, F-15 and more in a slew of challenging roles and circumstances. The co-pilot? My fellow trainee, like me, has flown sub-par aircraft for far too long. In his case it was freight runs throughout the night for the ever growing just in time online ordering world. I’ve flown sub-par stuff all over the world that landed on fields, snow, water, good runways and crappy dirt runways. Not a scratch on any of us for the primary reason of trust.

We tend not to trust many of the assumptions about machines we fly, places we are sent, or passengers or freight that we are instructed to carry. This type of flying work requires autonomy and self reliance, a perfect cocktail to breed writers and raconteurs whose principal goal is to come home without bending any aluminum.

Being unconventional airline outsiders gives us perspective. For example this aircraft, while small, has two AOA (“angle of attack”) vanes – things that measure how much “up angle” the wing has relative to the wind – too much “up” and the wing “stalls.” (More on this later.) The Swiss designers that built this Pilatus PC-12 put in two AOA vanes and a computer with redundant interpretations of said info. If either one disagrees with the other, the system is disabled. Makes sense, right?

So why would Boeing put two AOA vanes on the newest flavor of the 737, but only take data from one? No idea. That’s a great question. I’m still researching that. Many of us accident geeks are actually.

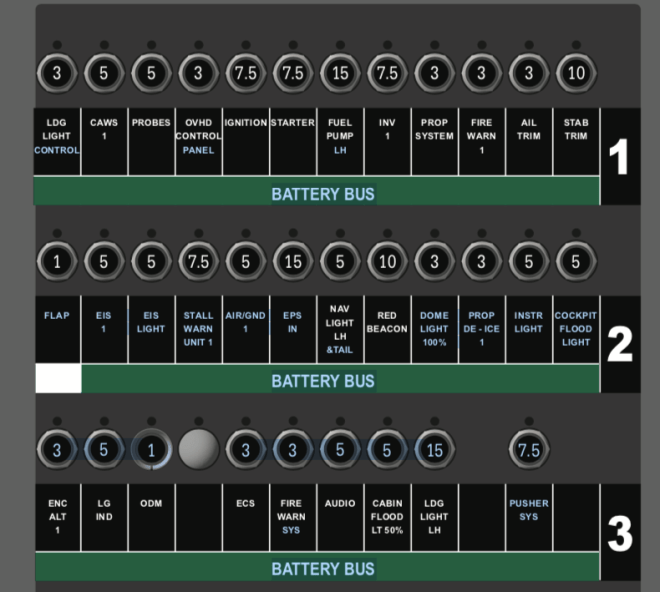

And much like the now famous 737 Max 8, the PC-12 also has a shaker and a pusher to rectify any problem that might lead to “too much nose up.” (Too high an AOA that could lead to falling out of the sky.) The trick and danger with such automation is that it might slam you into the ground when you don’t want to. That’s why Pilatus and our company have us train the crap out of it, the importance of knowing its limits, how to override it, and the rest of the docket of things you’d want to know in order to be in charge of it vs. it being in charge of you. I can tell you (half asleep) where the circuit breaker is that will disable this little demon – should it decide to be demonic vs. angelic.

Humans Beware

Which brings us to Boeing, and the subject of how sometimes airplanes try to kill you. Worse yet, same said aircraft manufacturer is slow to share this quality with all the people that paid good money for this new large transport category aircraft.

I wanted to pen something short and helpful about this dynamic in aviation, but I realized there is much more to the story and it mushroomed into an exploration of culture, unchecked greed, flying things, fear and how we humans don’t like mysteries and the unknown in matters aloft. So, while my fellow trainee screams the Pilatus up to 20,000 feet over an empty black night Nevada landscape, I slide the MacBook Air out of my flight bag to tap away.

I don’t always sit down to opine about aviation, corporate governance, and the mechanics of safety, though my family might beg to differ. Labor practices and global capitalism being what they are, I strive to create interesting consulting work in the cracks of my commercial flying schedule. Not only for survival but for the revival of the sense of purpose amongst the rank and file of aviation’s day in and day out front line peeps.

The interesting thing about pilots vs. say … financiers of the machines we fly, is that we have skin in the game. According to Nassim Taleb and similar modern day philosophers, this matters and we should be listened to. Hampered only slightly by my experience as a pilot worker bee who flies the machinery rather than trading its stock or future fuel derivatives, I’m engaged in the daily grind which all workers experience if they are to understand the system they live in.

Ethnography aside, the real meat of what gets news, ulcers and emotions, is accidents. And, I’m a bit of an accident geek, since they say so much about our flying culture, when we retrospectively line up the holes in the Swiss cheese to see how people die in flying things in the first place.

For example when it comes to Air France 447 “loss of control,” Joe private pilot running out of fuel, or the all to frequent “controlled flight into terrain”… my life experience, for better or worse, leaves me privy to the magic behind the curtain. In the case of Boeing’s latest crisis, an updated version of the “pusher” that occasionally surprises untrained and unaware crew, there’s a story that is not totally unlike the frog left in the gradually warming pot of water until boils alive. (Note: We, like the frog, will typically jump out before boiling temp / death.)

In a perfect bit of timing, I’m writing this piece as I am get trained on the 3rd aircraft in my career that has a “pusher.” This “pusher” is preceded by a “shaker.” The shaker is a warning to flight crews that the airplane thinks that it is getting too slow (and high angle of attack) to fly… and it is issuing an initial warning:

“Hey buddy… let’s speed this thing up or lower the nose or both please… m’kay?”

If you don’t listen to the shaker, you face the pusher. Not fun: The pusher, “pushes” the nose down so that it keeps flying. (Note: Don’t let this happen near the ground.)

Think of the little “dip” the proverbial paper airplane makes after it hits its peak apogee after the 7 year old launches it across the living room. The peak is the “stall” or “stalled condition” of the wing. Then… thank god… comes that dip! (Perhaps induced by the weight of a paper clip on the nose.) The airplane is saying “thank you jesus.. I got that nose down … and I’m flying again!”

And the paper airplane dips, rolls down hill, so to speak, gets some speed and flies again. This is fine, unless you are near the ground. If the dip happens too close to the ground, you get a Lion Air or Ethiopian situation where the pusher makes the dip happen, and the airplane hits the ground.

Blame

But before we get into the science and tech of all this, let’s talk a bit about blame, institutions like Boeing and the dynamic of airplane design committees, shareholder value and the accoutrements of greed that frequently dodge any investigation or exploration. Some initial questions might be:

- What led Boeing to think that an enhancement to legacy “pusher” technology was necessary?

- How does a wee Swiss manufacturer do a better job than Boeing

- What was the big rush to roll it out in the 737 Max?

- Lastly, why omit training, inclusion in manuals and the rest of it?

Improving systems is common sense and is done all the time. In fact, they were ostensibly doing us all a favor by acting on the safety and training ecosystem’s increased concern with this flight regime. They decided to help pilots fly better since more and more accidents seemed to be coming from loss of control. 1

One thing that media won’t trumpet or talk about much is that the FAA, IATA, NTSB and other key opinion leaders are really worried that pilots are forgetting how to fly. This “ability” is leading to loss of control accidents. These accidents are causing training regimens (in simulators, training programs, etc.) to include more concrete talk about how to maintain control by what the experts call “flying the airplane,” which means nothing more than #1 disconnect the automation and #2 physically / manually fly it so that you can ensure control – the most primary element in remaining bird vs. brick.

In Boeing’s case they simply took the trend, data and osmotic pressure from the accident experts and built a system that took away a bit more ‘choice’ for those flying. To make matters worse they did it quickly without much documentation or training and shipped the product.

Loss of Control

“Loss of control” (LOC) incidents / accidents continue to surpass “controlled flight into terrain” (CFIT). 2 The FAA, NTSB and other authorities surmised that the new number one risk to airline safety was from pilots losing control of the aircraft whilst flying, usually sometime during or after the aerodynamic stall of its primary source of lift and / or control surfaces. (“Loss of Control”)3

These were nearly all a variety of getting the aircraft into a stalled condition and not doing what the 7 year old did by putting that paper clip on the nose. That ‘weight,’ while trivial to us, is enough to get that nose to go down… once the paper airplane’s wing stopped flying.

If your small or large airplane, whether it is real or a paper demonstrator, doesn’t have a way to get the nose down (reduce angle of attack), you enter the world of “loss of control” aka “brick” territory.

When an aircraft is stalled (no longer producing lift from its primary wing(s) it falls stone-like until the pointy bits face into the wind again.4 Stall avoidance is accomplished by lowering the nose (and angle of attack of the wing) before it gets into a stalled condition.

Note: Anytime automation or technology is invoked to do something the human operator is already trained to monitor and accomplish, you might ask yourself: …. Why?

Are they taking my job, or do they think I’m incompetent? Pilots suffer from both versions of this dystopian dynamic, but Boeing won’t come out and say that. Their mandate is to sell more airplanes. Sure you might get some racist middle aged white guy drivel about how those people can’t fly. These troglodytes would be wrong: There is much more nuance to how accidents like this can even enter the realm of possibility. The story of the pilots who failed to keep the problematic aircraft airborne, while it repeatedly tried to kill them, is about:

- Lack of training

- Lack of experience

- Lack of systems knowledge

I could make a good case that Boeing is guilty of all three. To survive the set up that Boeing left these crew members with … you had to do extra curricular investigations, studying and preventative planning – all of which were well outside the scope of what the FAA, the employer, and the manufacturer required any mere mortal to do before taking the helm of the 737 Max.

The Pusher Man

Per above, pushing the nose down is all about getting airspeed. The Boeing 737 Max, and many of its predecessors and competitors come with some automation to ensure that if a stalled condition is about to happen that nose is “pushed” down per our paper airplane analogy.

The pusher, being diplomatic, and sensitive, has a cousin. This cousin, known as the shaker, gives you a warning. It senses a trend in your current condition and starts a warning. The shaker starts shaking the entire control column when the airplane gets too slow and near a stalled condition, by saying:

“Hey … what’s up … see this shaking I’m doing here?… Ya… Deal with your AOA or I’ll push this old donkey’s nose down without your consent… m’kay?“

If you ignore said shaking you go to phase two: Pushing the stick / yoke forward. It does this since you should have done this already. The pusher is sort of saying, “hey… buddy… we’re too slow … and … I gave you the shake warning, now I’m pushing.”

From accident report narrative, the shaker / pusher was active when it shouldn’t have been. This is now widely known to be because the initial design relied on only one sensor, when it could have used two. This is a big deal – why? Secondly, the logic that was programmed into how the automation handled this data was flawed on the basis that the airplane had other sources to measure WTF was going on. This stark set of facts begs the question: Why the rush to approve an obviously crazy design?

In the Boeing 737 Max 8 accidents, the battle between pilot and machine was longer than it should have been with the pilot losing in the end. From further reading, it also appears that the “brain” that processes all the flight angle, regime, etc. data flowing into the computer that decides whether or not to activate the shaker / pusher was likely flawed, off or erroneous enough to be triggered when it should not have been.

Which brings us back to our late 90’s vintage ambulance with its redundant, simple and effective system. (It is disarmed when: The airplane #1 the airplane is taking off, #2 landing or #3 if there is ever a disagreement between inputs.)

This is a good place for another warning: Never sell an automated thing to someone without a way to pull the plug on “said thing.” And… if there is a way to disarm said thing, be sure not to make it a secret. Heck, make it part of training.

The sad part, that many everyday pilots feel, is that we’d never want to set foot in an airplane where there wasn’t a clear sense of a) how to kill unwanted automation and then b) if that failed, a way to go “old school” and disable the entire system by knowing where the circuit breaker was.

The Underwriting Epiphany

What makes the news of the 737 pusher related stuff timely to write about is that it reveals another side to the evolution of the human and machine interface.

To the murky corners of underwriting be it Lloyds of London or a closed online forum of reinsurance advisors, one thing is clear to me: No one really sees the bigger event coming over the horizon in that some of us are facing so much automation that we forget how to fly.

Or … as a mechanic once told me, the “two problem problem.”5 When you have two errant parameters in a system, it is hard to know who to blame, what is going on, etc. Imagine your car’s fuel pump randomly fails, but so does its ignition system. The engine runs rough – but who is the guilty party to be replaced? Hyper fixation on either system leads to an entire suite of culprits being let off the hook.

Here is a vastly over-simplified, but helpful duality to explain aviation’s evolution, globally. To over-simplify, there are two groups of pilots:

- Group 1: The old geezers who grew up flying small taildraggers out of “fields” vs. airports (and all the mechanical hands on stuff that came with that.)

- Group 2: A new generation of “ab initio” airline pilots who have little experience outside of their highly structured and heavily automated world.

I offer this opinion for the risk manager with an important caveat: I’m not saying one is better than the other. There are simply two different pools of talent, shaped differently, that are currently flying aircraft. One group is suspicious of automation, but uses it cautiously nonetheless. They are also rapidly going extinct due to the fact that “trade” skills continue to be undervalued and fewer people are entering the trade of flying things that once were.

The other? They are being sought after young (pre college) to be put through what are known as “ab initio” airline programs where in exchange for a commercial pilot license, you are a form of an indentured servant of sorts. The airline “lends” you the money in exchange for you being attached to them, well, hopefully forever. You could argue that the US (and other military trajectories) are less usurous.

So these young cadets, that have known (and trusted) automation since day one. They have been flying with it and thus it plays a heavy role from the formative years of their training. They are grouped together with their older counterparts, and sometimes not. Either way, in the case of Boeing, the FAA and many other safeguards that failed, it didn’t work to protect us from some very sad and blatant collapse of a system.

Capitalism Is a Hell of a Drug

The pilots of the future will be plucked out of metaphorical kindergarten6, put through a highly structured environment and start building experience in the right seat of a large airplane that is equipped with a fancy computer (FMS or Flight Management System), flight director (“turn this way buddy!”), autopilot (“hey.. I’ll just help out by making the plane do what the flight director says, ok?”), and a pusher (“oh no… too slow… let me fix that for you!”).

The pilot shortage (or put another way, “the lack of a live-able wage for pilots” problem) only exacerbates this dynamic. Nothing exemplifies the accidents (and who they happened to) better than the cranky writings of an American or Southwest Capt. who penned this in April 2019’s Aviation Week and Space Technology letters to the editor:

Summarizing the above, a few elements emerge:

- The problem was known, yet went on without any action on the manufacturer’s part;

- Pilots were talking about it and in some cases building their own home-brew survival skills, game plans, etc.;

- The public was in the dark until there was enough carnage for Boeing to pay attention to its image;

As we dive further into the era of automation, pilots tend to get softer mentally in their flying skills. Our iPads, not to mention the airplane’s systems, do *so much* for us. The hiring world is changing as pilots become system specialists, rather than the scarf wearing “seat of the pants” people.

Boeing’s short sightedness aside, a related cultural tsunami is rolling in.

Progressive operators know the strength of more than a few key elements: The generalist, the well rounded, and the curious pilot and systems person is your most valuable. And paying a living wage to the best talent you can find – and keeping them – pays huge safety dividends. If bottom line oriented airlines and their investors see the connection, they create a safer culture, while putting bricks down that will transform the future.

Or as the safety people at the most profitable airlines like to say:

“If you think safety is expensive, wait until you have an accident.”

Epilogue

Update #1 – May, 20th 2019: This article by Robert Graves clarifies something that my drivel above dances around somewhat inaccurately. While the now infamous MCAS system is known widely as a “stall mitigation” system, it is really something else. It is a “make this plane feel like another plane” system that is tied into the stall prevention system. There is likely another treatise, story and debacle hiding in why you would do that in the first place, but I thought it worth mentioning since I’m doing the reader a disservice without accurately stating why MCAS came to be in the first place and what it actually does.

- https://www.iata.org/whatwedo/safety/Pages/loss-of-control-inflight.aspx

- https://www.ntsb.gov/safety/mwl/Pages/mwl5-2017-18.aspx

- https://nbaa.org/aircraft-operations/safety/in-flight-safety/loss-of-control-in-flight/

- For good aerodynamic control you want to ensure a narrow enough angle of attack that the flow over the wing is smooth and not “burbly.” (Think of “burbly” as your hand out the window in a moving car – flatten it like a wing and it zooms through the air, twist your hand so it is perpendicular to the road and you have a ton of drag and “burble” behind your hand – it has “stalled” and is no longer “flying.”)

- Matt Stern, of Owl’s Head, ME, once told me matter of factly that it is damn hard to figure out what is going on when you look at trouble shooting through the lens of the one problem assumption. If you have two possible errant parts of system, the trouble shooting takes on a much larger set of testing.

- Looking to how the People’s Republic of China currently grooms pilots, this is perhaps not a metaphor for long. The irony of capitalism, consumerism or any unchecked extreme system is that choices are removed earlier and earlier in life. Many Chinese pilots come to Canada and the US to blast through ratings and meeting these candidates you’d be amazed to find that a full 25% to 50% are fairly unhappy and have no interest in flying. Family, social status and other factors lead to them being “chosen” and “sent” for training. Incidentally their training time / period in North America is frequently marked by sub-standard living conditions, daily food stipends, etc.